Every week on my instagram account I get asked questions about exercise and chronic fatigue recovery. Whether you are bed bound, just building up your step count or wanting to add in other forms of activity to your daily routine, I want to address that for you here.

Exercise was a huge passion of mine prior to my diagnosis with CFS. I was a regular gym bunny, I loved yoga, hiking, kayaking and paddle boarding. Moving my body was an outlet for stress and I was also very competitive with myself to increase my performance.

Losing this outlet was one of the hardest things when I became unwell. It was how I managed my emotions, how I socialised and how I spent my free time.

I googled and searched the internet for all the answers and sadly, I didn’t find many. I worked with an exercise physiotherapist who specialises in chronic illness thinking that she would have all the answers and would magically get me back to exercising again.

I tried different things and crashed many times. But I did learn a few lessons in the process and this is what I would like to share here.

Stability First

One of the key principles for recovering from an Energy Limiting Condition -whether that be CFS/ME, Long Covid, Post Viral Fatigue or something else – is stability. People who experience these conditions will experience exercise and stress intolerance. Their systems are highly sensitive to stimuli such as light, sound, heat or cold.

This is a reflection of their unstable physiology and unstable nervous system, what we often refer to as a “Syndromal Pattern”. This is a pattern that develops over years (or decades). When the body has spent so long in survival mode, it learns to function from a place of dysfunction, which may work in the short term, but isn’t sustainable and eventually breeds dis-ease.

Restoring health, vitality, resilience and in the context of this post, exercise tolerance, starts with restoring stability. How we do this is by addressing what I refer to as the Foundational Five. These are the five core principles that, when mastered, help to stabilise the Syndrome Pattern and eventually, reorganise it.

It is important to understand that health and resilience is build on the synergy of different approaches. You may have mastered some of these five elements but not all of them. Therefore, I created a FREE quiz to help you identify which of these elements could be a priority for you. You can take the quiz here.

Exercise is a stress on the body and stressors are inherently destabilising. Therefore, before we can tolerate exercise, we may need to build more stability into the system. We do this by mastering the Foundational Five. Once we have done this, we can start to think of other principles which may be supportive.

Movement Matters

Wherever you are in your journey, movement matters. You cannot recover from chronic pain and fatigue syndromes without a movement routine. That doesn’t mean that you have to run a 5k or take a CrossFit class. But it does mean you have to move your body whether that is a gentle walk or laying on your back and taking a few gentle stretches.

Movement creates extensive biochemical and physiological changes in the body that no drug or supplement will be able to match or surpass. When you move, your body:

- Makes more mitochondria

- Modulates immune cells and inflammation

- Increases growth hormone

- Increases nitric oxide which improves blood flow important for health tissues

- Increases Brain-Derived-Neurotropic-Factor (BDNF) which supports neuroinflammation and plasticity

- Increases insulin receptor sensitivity, important for healthy blood sugar control

- Increases opioids; natural pain killers

The downside is obviously that movement or exercise can increase oxidative stress and this increases risk of metabolic over-training syndrome, energy crashes and Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM). Therefore, the key is finding the magical Goldilocks dosage for you. This blog is here to help you do that!

No One Knows Your Body Better Than You

No one knows how it feels to be in your body. Experts can give suggestions, offer frameworks and explanations that help you to understand your body better, but you are the only one who can actually experience what it feels like to be you.

Therefore, there is no miracle formula on EXACTLY how you should exercise if you have chronic fatigue but, there are frameworks and principles that you can implement as you find what works best for you.

You are probably sick and tired of people telling you to “listen to your body” but that, unfortunately, is exactly what you’ll need to do. Often, those who are experiencing chronic fatigue are not very good at this so be patient and gentle as you rebuild a kind and compassionate relationship with your body and your nervous system.

Know Your Coping Style

We all hear that exercise is important for health, but when you are navigating chronic fatigue it can be a challenge to find the “sweet spot” between doing too much and doing too little.

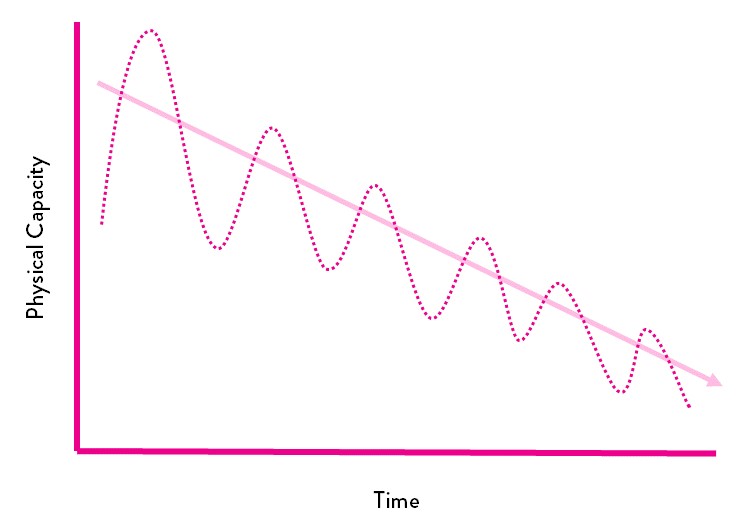

Over-coping

Over-coping is the tendency to persistently do more than what we should which means that we operate outside of our window of tolerance too often or too long. Ultimately this means that the body’s needs for rest, recovery and repair go unmet. Physical capacity decreases over time due to the wear and tear on the body’s system and the window of tolerance narrows. This means that we are able to do less and less and it gets easier and easier to over-extend. This can be a common pattern for A-Type Over Achievers.

Under-coping

Under-coping is when we persistently do less than what we are capable of or we avoid stress at all costs

Ultimately we do not meet the body’s needs for the stimulation that grows capacity and there is a narrowing of the window of tolerance. Over time, life becomes smaller and smaller as we avoid all triggers, stimuli and challenges for fear of doing too much. This is more common for anxious personality types.

Whether you are an under- or over-coper, the end result is the same. A deterioration and loss of exercise capacity over time. Once you know your coping style you can identify how to work with your body and the type of support that you need.

Over-copers need to learn to be okay with doing less and having the patience to be consistent. I was a classic over-coper and I still have to be mindful today about taking things a little more slowly than I would like. The mantra I would use would be: It’s not about what you can do today, its about being able to do it again tomorrow!

Under-copers have to build the confidence to increase the amount of challenge and stimuli. This needs to be done gently and slowly in a way that does not feel threatening to the body.

Do Whatever Doesn’t Make You Feel Worse Than You Already Do

One of the most valuable lessons I learnt was that you can do anything, as long as it doesn’t make you feel worse than you already do.

It can be tempting to wait for a “good day” before you give yourself the green light to do some activity. Although some days are better days for movement than others and there are definitely days when you just need to rest, consistency is important too.

Therefore, you want your exercise routine to be something you can consistently maintain and something that doesn’t make you feel worse. This means that even if you feel a bit more tired, have a headache or body pain, you can still move your body, provided you aren’t left feeling worse for wear afterwards.

In my own recovery there were days when I didn’t feel great but I would still go for a walk or a gentle swim because I knew that it wouldn’t make me feel worse, in some cases, it would make me feel better.

Start Small

Wherever you start, start small. The exact place that you start will depend on the level of fatigue you are experiencing and your current level of conditioning.

If you are bed or house bound this could be anything from gentle movements or stretches in bed, to a short walk around the house or some isometric (without movement) muscle contractions.

As you become more mobile maybe some of your activity will become doing chores around the house, a bit of cleaning or gardening.

If you are a bit more mobile, most people do really well with walking in combination with stretching, yin or restorative yoga. This is easy to progress as you can slowly build up your step count and begin to add slightly more challenging yoga postures into your routine.

Once you can walk for an hour or achieve 7000 steps per day, it might be a good time to add in something else if your body feels ready.

Top Tip: Routine is important in the earlier stages of fatigue recovery, therefore it is best to move at the same time each day. I recommend earlier in the day so that stimulation doesn’t negatively impact sleep. However, you’ll know the best time for you.

Break It Up

Regular movement throughout the day is great for your lymphatic system,it supports circulation for tissue oxygenation and it can help reduce mental stress and improve posture.

At least in the beginning of your journey, little and often can be more beneficial, and easier to tolerate, than big chunks of activity.

For example:

Instead of doing 7000 steps in one hour long walk, how would it feel to do 3×20 minute walks instead?

Instead of doing a 20 minute bodyweight workout, how would it feel to do some squats in the morning, some press ups mid-morning, some lunges at lunch time and some sit ups mid-afternoon?

As your capacity and endurance increases you can begin to string more and more together. Be open to experimentation, listen to your intuition and honour your body.

Be Consistent

There is no point doing anything that you cannot do consistently. If you try some yoga or a 20 minute bodyweight workout, but then you have to reduce your activity for the rest of the week, this is too much.

In the beginning stages you should be able to repeat the same workout daily. i.e. 20 minute walk each day. This means that if you do a 20 minute walk but the next day you can only do 5 or 10 minutes, it would be better to reduce your walking time so that you can be consistent daily. It can be frustrating to micromanage yourself like this but these details matter and can make a big difference in your ability to progress.

I mostly recommend that if my clients can walk, they start by building up their walking endurance. Once they can walk for an hour or achieve 7000 steps per day, it might be a good time to add in something else.

If they add in something else they may need to walk less on those days, but it shouldn’t impact walking on other days.

Finally, if you are more of an under-coper, it is easier to be consistent with activities that you enjoy.

Treat Exercise Like a Dial, Not a Switch

Although consistency matters, sometimes life gets in the way and we can’t always be as consistent as we would like. In which case, it can be helpful to think of exercise like a dial instead of a switch. This means you have range of activity that you do each day.

On days when you have more committments, stress or just don’t feel great, you might turn the dial down from 7000 steps to 3000 steps. On days when you feel good and have more time to rest and recovery, you may turn the dial up to 9000 steps.

The benefit here is that you always have some movement in your day even if it is less on some days and more on others.

Progress Slowly

Many people who have chronic fatigue experience post-exertional malaise, which is an exacerbation of symptoms from immediately after exercise to 24 or 48 hours after exercise.

Post-exertional malaise is often a sign that the inflammation generated by the stress of the exercise was too much for the body to handle. Slow progress gives the body space to adjust so that physical activity causes less inflammation and is less overwhelming to the body.

Exactly how you progress will depend on what you are already doing and where you are in your recovery. A rule of thumb may be to make a 10% increase every couple of weeks.

With women I find it can be helpful to make this increase at the point in their menstrual cycle when they feel their best and possibly even take a structured step back during the time in their menstrual cycle when energy is lower. These cyclical highs and lows do tend to even out as overall health and resilience improves.

Be Aware Of Additional Challenges

Depending on your experience of fatigue and areas of the brain that may be affected by your illness experience, some types of exercise or exercise environments may be more challenging. For example:

- If your frontal lobe as been affected, you may struggle with co-ordination and therefore exercise or movement which requires complex coordinated movements may be more tiring than those that are simple and straight forward.

- If your parietal lobe has been affected there may be instability and poor spacial awareness. Movements which require you to orient yourself in space may be more tiring.

- If your temporal lobe has been affected you may struggle with loud noises. Therefore, exercising in an evironment with loud music may be more tiring than a quiet calm environment.

- If your cerebellum has been affected you may struggle with balance, vertigo, dizziness or motion sickness. Therefore, riding a bike outside, which means you are unstable and in motion, may be more tiring than a stationery bike.

- If you occipital lobe has been affected you may struggle with processing visual information. Therefore, if you are on a bicycle outside with lots of changing scenery, this may be overwhelming and tiring for your brain. Stationery exercises may be better choices in the short term.

- If your thalamus has been affected you may struggle with light sensitivity which means exercising in an environment with bright artificial lighting could be more tiring than natural or soft light.

Monitor Intensity

There is various guidance around monitoring intensity. This includes heart rate monitoring and perceived levels of exertion. This is the following advice that I am aware of:

- Keep your heart rate under 60% of your maximum heart rate where maximal heart rate is calculated as 220-age e.g. 220-37 = 183, 183/100*60 = 110bpm

- Keep your heart rate under resting heart rate +30bpm. Therefore, if your resting heart rate is 60 bpm you would want to keep your heart rate under 90bpm. The challenge with this is that some people with chronic fatigue have very low resting heart rates (mine can be in the 40’s at times) and some people have very high resting heart rates (e.g. 90bpm).

- Maintain a level of exertion that is 4-5 out of 10 on a scale where 1 out of 10 is resting and 10 out of 10 is maximal exertion. I have never used this scale because, depending on what activity I was doing, I could still experience PEM when operating at 4-5 out of 10.

Where I personally had the most success was using heart rate monitoring. I would keep my heart rate under 110 bpm when walking. For the most part I think the benefit was psychological because I felt like I had a “safe zone” in which I could operate. As my confidence and sense of wellbeing increased I was able to let it go above 110bpm without post exertional malaise and eventually just stop paying much attention to it at all.

Final Words of Wisdom

Fatigue recovery has ups and downs. Sometimes you will do too much and suffer the consequences short term. Remember, there are no failures, only feedback. Everything that doesn’t work gets you closer to what does!

Recovering from an Energy Limiting Condition can feel overwhelming and lonely. It can be hard to know where to start, what to do and if you are on the right track. I created an affordable monthly membership to support you through the process. You can join the Nurturing Resilience Membership for just £39+VAT/month and have access to comprehensive courses that will help you stabilise your system and group calls for community and ongoing support. Find out more here.

Want to learn more about exercise and Chronic Fatigue? There are a few other blog that you can read including…